You can’t police without the people: Why Jamaica must return to the roots of public safety

Article By: Dr Leo Gilling

This disconnect matters. As Marcus Garvey cautioned, “a people without the knowledge of their past history, origin and culture is like a tree without roots.” That warning is particularly relevant to the current conversation on policing in Jamaica. Without a clear understanding of where our policing model comes from — and what it was originally intended to achieve — we risk drifting further away from its foundational purpose: community safety built on legitimacy, consent, and public trust, rather than control and domination.

The Jamaican policing model was born out of the British tradition, introduced through the work of Robert Peel, widely regarded as the father of modern policing. Peel rejected the idea of police as an occupying force. His most enduring insight — “the police are the public and the public are the police” — was a radical statement of shared responsibility. Public safety, in Peel’s view, was not the sole burden of the state, but a collective civic obligation. Police officers were not meant to rule over communities but to serve within them.

This philosophy was a direct response to what existed before. Prior to Peel, policing in Britain resembled slave patrols, night watchmen, and thief-takers — loosely organized, often corrupt, and plagued by normalized misconduct. Peel professionalized policing by placing it under state authority, formalizing standards, and anchoring police legitimacy not in force, but in public consent. His reforms were designed precisely to prevent policing from becoming militarized.

Peel’s vision was codified in nine core principles of policing, all of which remain deeply relevant to Jamaican society today. At their core, these principles emphasize prevention over punishment, public approval over fear, cooperation over compulsion, fairness over favoritism, and restraint over force. They affirm that police must never replace the courts, must never act as judge or executioner, and must be measured not by displays of power but by the absence of crime and disorder.

These principles are not abstract theory. They are evidence-based practices that have shaped some of the most effective police services globally. As I noted in my recent article, “Suppressing Violence Without Solving It,” modern policing works best when multiple approaches — community-oriented policing, problem-oriented policing, intelligence-led policing, evidence-based policing, and hot-spot strategies — are used together. When properly balanced, these models reduce crime while simultaneously strengthening police–community relations by addressing root causes, relying on evidence, and reinforcing legitimacy.

This is why, historically, British policing emphasized visibility, familiarity, and restraint. For many years, officers patrolled communities with batons rather than firearms — not because crime did not exist, but because legitimacy and cooperation were seen as the first line of defense. This is not a call to return to the past, nor to ignore contemporary security threats. Rather, it is a reminder that successful policing has always required integration with community life, not separation from it.

Jamaica now stands at a critical juncture. With murder rates declining, the country has a rare opportunity to recalibrate its policing model. This is precisely the moment to reduce overreliance on militarized tactics and emergency measures, and to return to the foundational principles of professional policing that emphasize trust, accountability, and partnership. Ignoring these principles risks entrenching mistrust even as violence temporarily subsides.

Peel’s nine principles are not relics. They are guardrails. They remind us that force without legitimacy breeds resistance, that fear cannot substitute for trust, and that sustainable public safety is impossible without community buy-in. If Jamaica is serious about long-term violence reduction, then now — while murders are down — is the right time to restore balance, reaffirm policing by consent, and re-root public safety in the very principles on which modern policing was built.

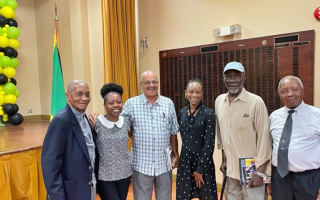

Dr. Leo Gilling is a criminologist, educator, and diaspora policy advocate. He writes The Gilling Papers, where he examines policing, public safety, governance, and community-based solutions in Jamaica and across the African diaspora. Send feedback to editorial@oldharbournews.com